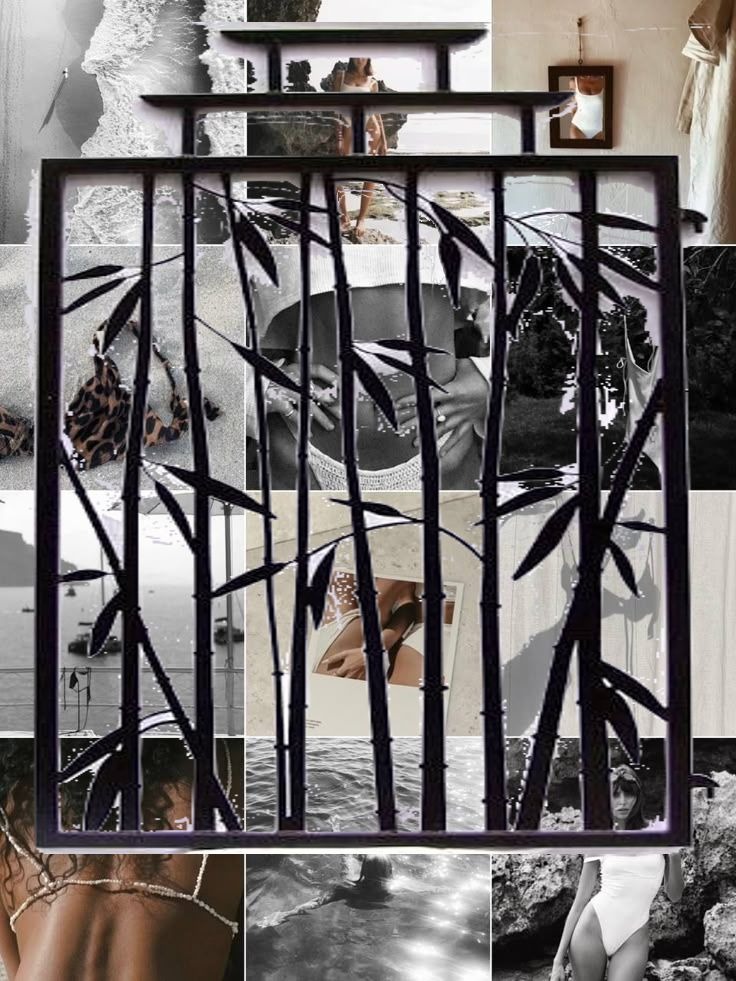

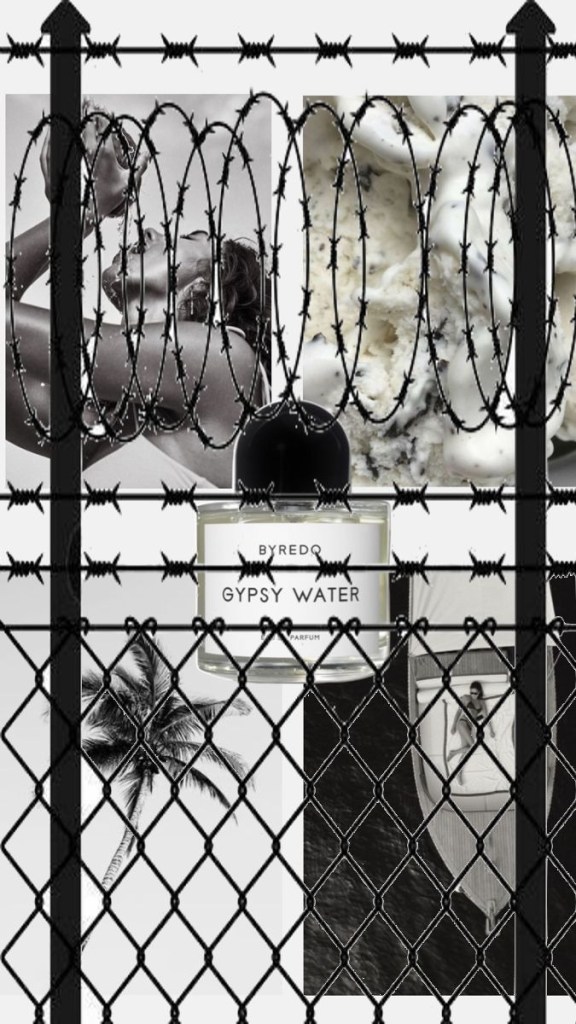

I wanted to explore different physical defences in the form of wrought iron and barbed wire and fences. They have been arranged in order of most appealing and palatable aesthetic design to the least. The images vary in degree of luxury, some may not seem particularly affluent to westerners but seen through the eyes of locals in tropical destinations, they are distant enough. Some images are ones that would only appear through social media, and so is a play on both physical and psychical boundaries between rich and poor, between access and limits. Ironically many of these images are magazines or ads or Pinterest collages and are not directly consumed by the rich but by western middle or lower classes aspiring to a greater social status, and so we watch the watcher, through the eyes of the other, with the unsettling frustration of watching those who have what they do not, desperately wanting more.

Sometimes people who do not live inside the wealthy mansions are still able to go physically inside the protected houses, as cleaners, chefs, or childcare workers, but they are still barred from the ‘other’ experience of affluence through exclusion in social gestures, lack of ownership, lack of psychic access, and lack of rest. Rest would mark ownership somatically, at the end of the day it is the client and owner who rests on the sofa or sleeps on the bed. The social media view being barred expresses the social and psychological exclusion and isolation from an alien “other” which is not easily described through physical barriers alone.

The assortment of bars and wire protections can be around windows, driveways, or entire gated communities. They demonstrate that the wealthy do not choose to protect themselves, it is a necessity that is not chosen. It can be decorated and aesthetic, but it doesn’t change the fact that it is not chosen and if given the choice we would want to roam loose and freely. But the need for protection itself has been aestheticized as a status symbol, but here I wanted to expose its inherent vulnerability and instability. If the rich colonizers have the power to shape their world, why are they needing to protect themselves from the world they’ve created? In this aspect they are in the same situation as the impoverished people they have created, interacting with the other not freely but out of forced necessity, a necessity out of their choice.

There is an implicit desire to be seen, to be visible, between the spaces of the metal despite wanting to keep the voyeur out and excluded physically. They are invited visually and psychically to observe the lives of the rich. There is a need for validation, a desire to be consumed, not only by their other affluent peers but by the impoverished themselves. This is another point of vulnerability, of outsourcing the emotional labour of validating their existence.

On the other hand, those too poor to afford security around their housing, often do not have a choice on how they are accessed and viewed. The interpretation of their lives, suffering, triumphs, meaning, is free to interpret by academics or journalists or tourists or business or politicians. And yet it is implied by this work that there is some freedom that exists in this life, some mobility of identity and validation that is unfathomable to the gated and curated lives of the wealthy. The wires around the lives of the rich also imply a prison of their own making.

This work echoes Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, which arises from a confrontation between two self-conscious beings, each seeking recognition. One asserts dominance, becoming “master,” while the other submits, becoming “slave.” However, the master depends on the slave for recognition (without which their identity collapses). The slave, through labour and interaction with the material world, attains self-consciousness and transformation, a deeper freedom. The master’s apparent superiority turns out to be unstable and dependent on the very subject they dominate. The wealthy rely on the labour of the poor to maintain the homes and curated lifestyle that they protect, as house cleaners, cooks, chauffeurs and security guards. They rely on the savage, impoverished gaze as an anchor in the uncountable, unquantifiable and terrifying wilderness they find themselves in, in the new world, and the anchor of consciousness in which to measure and orient themselves around. The one who attempts to leave the position of slave by dominating others as slaves, becomes imprisoned to the position they must protect, while the slave, who has lost everything, and thus has nothing to lose, is free.

The master nullifies the ability of the other to see their consciousness freely. Through invalidation of consciousness (destruction of Maya codices, replacing gods with catholic saints, the forced supremacy of western science and beauty standards) the slave’s position is consolidated, and indigenous peoples lose access to their own identity, their ability to view the world in a conscious manner. If this visual essay is read backwards, from barbed wire to delicate wrought iron patterns, we see how the hostility of the master is disguised through beauty, making it harder for the outsider to explain why they feel excluded and discriminated against. The disguise is a critical part of the master’s ontological reason for existence, the primary weapon of class violence. The conscious gaze is not reciprocal. The slave must not look directly into the eyes of the master. There are windows, but they must always view each other through obstruction, through gates of steel, a clear territory of who is outside and who is within, who is allowed and who is excluded.

Leave a comment